|

||||||||||||||||

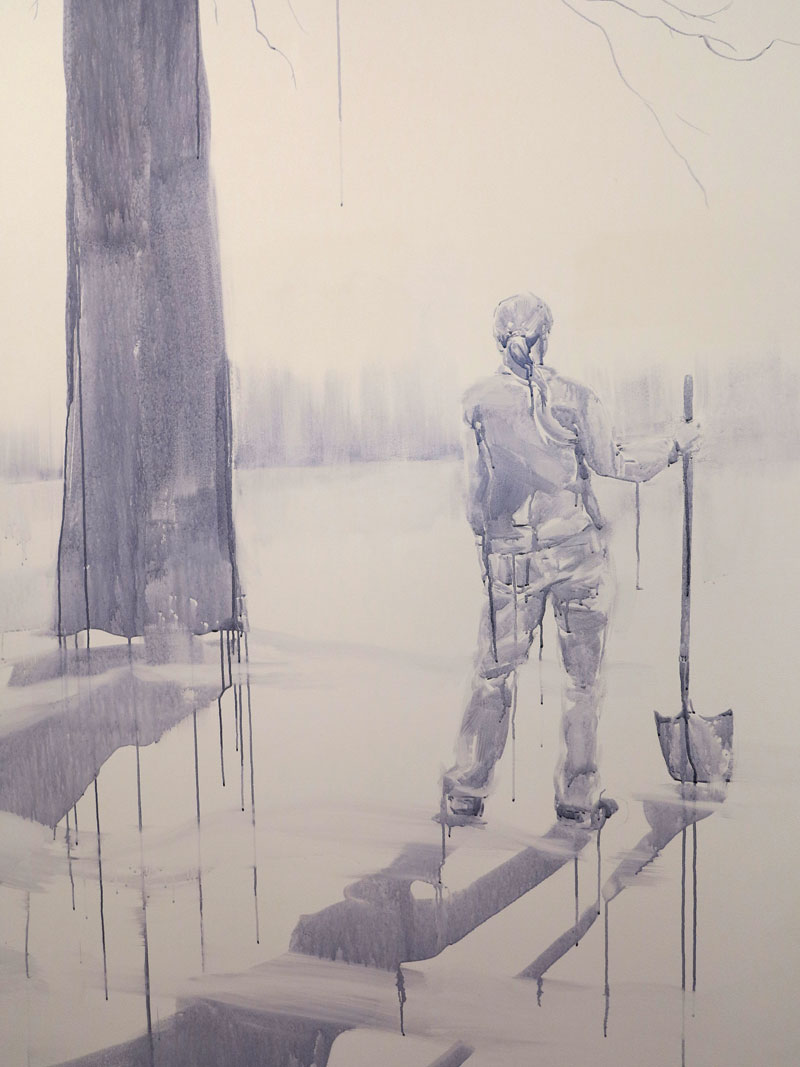

Cindy Stockton Moore |

||||||||||||||||

'Mute Things: Rebecca Saylor Sack and Cindy Stockton Moore' |

||||||||||||||||

Curated by Jacob Feige

Stockton University Art Galleries, Galloway, NJ

January 17 - March 22, 2017

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Installation view, featuring a portion of the wall drawing 'Nothing Not There'

Ink and Graphite on Wall.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Exhibition Essay by Jacob Feige In their projects on landscape, Rebecca Saylor Sack and Cindy Stockton Moore break the traditional dichotomy between humanity as corruption and wilderness as purity in the landscape. The American forests, which Cole described nearly two centuries ago on the terms of purity and divinity, are all the more wild for their human presence. Each artist, in her own way and in markedly different media, addresses landscape in the twenty-first century not just as contaminated and over-trodden, but also as an impure, corrupting life force in itself. Nature can be just as menacing as humanity, and the two together even more so. Now in its second century as an artistic subject frequently shunned as outré, landscape is nonetheless embraced by artists seeking to chart humanity’s uneasy relationship with its once-virgin terrains and with the artistic genre of landscape itself as articulated by Cole. The exhibition at the Stockton University Art Gallery, Mute Things, pairs these two Philadelphia-based artists in an exhibition for the first time. Dense patterns of textured, astringent color pervade Rebecca Saylor Sack’s oil paintings, taking on the logic of natural forms as much as explicitly representing them. In her paintings vegetation is abundant and all-encompassing, overwhelming the viewer with optical intensity and leaving little room for the eye to rest. Flowers, leaves, and sticks jut outwards towards the viewer and winnow down to the smallest possible tips and buds, often in the same painting. Her impasto surfaces impart a physical presence on her subjects beyond mere representation, as though they are fungal growths seeded on the surfaces of paintings to maximally spread color and pattern. Little tranquility is to be found in this work. If the sparing use of a veridical and natural palette occasionally forms a stable reference to the genre of landscape painting, intensely colored patterns overwhelm it, leaving the viewer unable to gain a clear sense of scale and terrain. Abstraction derived from the complexity of the natural world is the currency of these paintings. No wonder they are formally closer to non-objective painters like Joan Mitchell than they are to the American landscape painters following in Thomas Cole’s wake, whose emphasis on clarity and monumentality points to a divine order. No such order is to be obeyed in Saylor Sack’s version of nature. The only evidence of animal life in Saylor Sack’s work is in the occasional bone, skull or shell, always overtaken by the surrounding flora and desiccated as it returns to the soil. Her plant life is as vicious as it is beautiful, inverting the traditional hierarchy of foliage as background or distant subject, with humans and their constructs typically occupying the foreground. This inversion leaves little room for any background at all; the small spaces between plants take on their own abstract, fragmentary patterning. No distant space exists in the work, with these small bits of background becoming as physical and frontal as any other element. Where Saylor Sack’s paintings push the landscape as close to the space of the viewer as possible, Cindy Stockton Moore’s works on paper allow landscape to recede into a hazy, uncertain distance. The viewer must strain to view the subjects of each work in a monochrome fog, in the process seeing a very different, but no less considered sort of painted mark. A barren, bleak landscape emerges through the layers of transparent wash, applied precisely to form a coherent image, yet allowed to pool and drip unpredictably. Though not always apparent on first inspection, human figures inhabit a leafless, degraded landscape, their presence evoking mystery more than defining a clear narrative. Are they fleeing catastrophe? Are they spending a leisurely day by the riverside? Have they run for their lives into some body of water? Do they climb trees for protection, or for fun? The narrative explanation of each piece, if there were to be one, could plausibly be societal collapse or simple recreation. The tone of the work sits dramatically (and ambiguously) between these two possibilities, a dream-like mood of aimlessness, wonder, and fear. Whether by over-enjoyment or catastrophe, the landscape has lost its fertility and warmth, but not all of its grandeur. Saylor Sack and Stockton Moore chose the title for their exhibition, Mute Things, the reflect the oblique way that painting communicates ideas. Taken from an offhand remark in a letter by the seventeenth-century French painter Nicolas Poussin, the phrase (“moy qui fais profession des choses muettes,” or roughly, “I who make a profession of mute things”) refers to mystery and intuition in painting as its primary currencies, rather than its capacity to communicate concrete ideas. While implicit in both artists’ work may be a critical stance on human abuses of the environment, it is an oversimplification to say that their works are about that, per se. If there is a connection between these two artists and the likes of Thomas Cole, it is that they each regard nature as something that can be meddled with by humankind, but that it is ultimately a more powerful force than humanity itself. As an artist, tapping into that power of nature is, somewhat paradoxically, to channel a force greater than one’s own, for the sake of that most human thing: art. |

|||||||||||||||

| Installation View 'Mute Things' | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| 'Nothing Not There' wall drawing | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Installation View, Mute Things | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Mangrove, Ink on Paper | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Detail, 'Nothing Not There,' ink on wall, 2017 | ||||||||||||||||

| Click to return to top | ||||||||||||||||